Henry Casselli

born October 25th, 1946

The following is excerpted

from the catalogue essay

by Donelson Hoopes in

Henry Casselli

Master of the American Watercolor

A currently touring retrospective of the art of Henry Casselli is an especially significant milestone in his career. When the New OrleansMuseum of Art was founded in 1910, it relied upon the cityís independent art organizations to sponsor its exhibition programs. Among them was the Art Association of New Orleans, which has remained active to the present. In 1964 the Art Association recognized Casselliís youthful talent by awarding him a scholarship, his first important public acknowledgement, enabling him to gain the kind of professional art instruction that would sustain his earliest ambitions to become an artist. Thus, after thirty-six years, the faith placed in him by the Art Association has been amply vindicated; Henry Casselliís career has come full circle with this, his first major retrospective exhibition.

Casselliís life and art intersect inexorably with that of New Orleans. Born in the racially mixed Ninth Ward near the French Quarter, he has a firm grasp of the realities that permeate the daily experiences of ordinary people, particularly in that section of the city. His work has taken him far afield, such as his involvement with the NASA "Artistry in Space" project, but his attachment to his roots in New Orleans remains at the heart of Casselliís abiding concern as a painter whose primary focus is fixed on the qualities that he finds in his encounter with the life around him. These concerns for the human experience are essential to his work and form its dominant character.

Casselli began his studies in New Orleans at the McCrady School of Fine and Applied Arts in 1964. John McCrady (1911-1968) was an influence on Casselliís direction, certainly; but, McCradyís principal function as a teacher was largely to affirm the rightness of Casselliís natural inclinations. As early as his second year at the McCrady School, Casselliís mentor was confident enough to invite him to join the faculty as an assistant instructor. Casselli matured at the McCrady School through sheer application to work and, as he says, from learning from "every piece of art Iíve ever seen," which included reproductions he found in books.

The war in Vietnam escalated in the early years of the Johnson Administration, and Casselli found himself drawn into the conflict even as he was beginning to flourish at the McCrady School. While it is not unusual for the military to convert barbers in civilian life into bakers, the Marine Corps, to its credit, recognized Casselliís gifts. He was duly assigned the position of "combat artist." This was not a "rear echelon" dispensation, however. Casselli was sent to Vietnam, and immediately saw action in the massive Tet Offensive launched by the Viet Cong. As he recalls, "Within three days of my arrival, I was knee-deep in war. I had to be a Marine first just to survive." Somehow, he managed to summon the will to commit himself to sketching what he witnessed of the war, the "hell and the unspeakable horrors of Vietnam," as he says. Many of these drawings (above: Young Men Growing Old) are remarkable for their quality of a gritty intensity, utterly devoid of any inclination toward academic finesse. Looking at them, one feels not only "knee-deep in war," but also knee-deep in the mud of Vietnam and the anguish of the combatants.

The sense of immediacy in Casselliís combat drawings and paintings is what distinguishes them as works of art; moreover, as documents of a momentous period of United States history, they are of lasting importance. Both of these aspects would emerge again in 1980, when he was invited by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration to serve as one of its official artists, with the assignment to record the preparations for Americaís first Space Shuttle launch. His Vietnam drawings in the United States Marine Corps Museum collection were part of the impetus for NASAís overture, since it was looking for an artist who had proven his ability to work under the demanding conditions presented by the highly charged environments of the Houston Space Center. His drawings of astronauts John Young and Bob Crippen preparing for Space Shuttle simulations are full of anervous energy, conveying a sense of high excitement by their sheer rapidity of notation. The following year, Casselli was present for the preparations for actual launch of the Space Shuttle, this time taking on the more demanding task of working in watercolor. And again in 1998, he was invited to record for posterity the flight preparations of his most celebrated astronaut subject, John Glenn, STS-95.

Following his discharge from the Marine Corps in 1970, Casselli returned to New Orleans. As he recalls the event, "Mr. McCrady died three days after my return from Vietnam. We never had the chance to speak about, share or work through any of my experiences there as an artist or as a young man at war. I lost the one person I felt I needed most at that point in my life. I found myself truly on my own; for while I had shown signs of independent development as an artist in Vietnam, the return home to Mr. McCradyís death really cut me loose from him and the schoolís influence."

Casselli's methods of working and, of course, his subject matter took on a completely new character. He now concentrated upon watercolor as his preferred medium, which he feels was both a natural and spontaneous choice. He also began to rediscover a sense of identification with the life of blacks in his native New Orleans neighborhood and to evolve his creative responses to it. One of the earliest watercolors in the present exhibition, Morning Cup (1971) is suffused with the kind of quiet and pervasive undercurrent of emotional intensity that would come to typify his homage to that life. Almost as if rejecting the expected norms of the medium, Casselli began to use watercolor for his black subjects not primarily as a vehicle for luminosity, but with an opaque density, which becomes a visual metaphor. These pictures are meditations upon the condition of this portion of southern humanity, which he treats with a deep respect utterly free of condescension.

Barely a year later, as he resumed his career, Casselliís work began to appear with remarkable frequency in exhibitions from Texas to NewEngland. In 1971 alone, there were a dozen venues, including the prestigious American Watercolor Society in New York, where his first submission won him an award. He would continue to exhibit annually at the societyís exhibitions, garnering prizes along the way, eventually winning its Silver Medal of Honor in 1986, followed by the societyís distinguished Gold Medal of Honor the next year for Echo. In that fifteen-year interval, Casselli solidified his position as a major figure in American watercolor painting. He is a member of the American Watercolor Society, Watercolor USA Honor Society, and a full academician of the National Academy of Design.

Casselliís confident mastery of watercolor has enabled him to advance the medium into the area of commissioned portraits. Among the most challenging commissions of his career was for a portrait of President Ronald Reagan, an assignment that spanned two years because ofofficial delays. Casselli was finally granted several hours of the presidentís time over a period of four days in 1988. A series of pencil drawings he made in the Oval Office resulted in the life-size oil portrait now in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. The drawings are remarkable likenesses, conveying the animation and presence of the sitter; moreover, there is a fluency of rapid notation in them that recalls what he achieved under a much different sort of stress in Vietnam.

Over the past decade Casselli has concentrated his focus upon the kind of subject he began to essay with Morning Cup in 1971. Echo, the work that won him the American Watercolor Societyís Gold Medal in 1987, was seminal in that it set forth a conceptual paradigm for what followed, particularly in the way he makes dramatic contrasts of positive and negative space between the figure and the background. The sources are often to be found in his complex reactions to stimuli, not only sight, but sound. He chose the title of Echo, for example, on recalling the footfall of the subjectís shoes on the floor of an empty cotton warehouse, the setting for the painting.

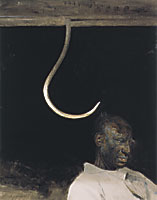

The sources driving Casselli's imagination are located both in art and in his deep-seated memory. Memory plays a pivotal role in Dodger, a species of portrait of a man Casselli knew from childhood and had always wanted to paint. The man was known to Casselli simply as "Mr. Paul," but the painting's title evolved from the artist's associated memories of long-ago evenings in his old neighborhood: "After listening to the 6:15 evening prayers that were broadcast on the radio, Mr. Paul would always tune in to the Dodger baseball game. This circumstance was the stimulus which produced a true portrait of this man." Eventually, in 1992, he sketched him from memory, without any intent to realize a painting; later Dodger "just appeared" under Casselli's brush. What cannot be explained was the presence of the menacing hook; even the artist confesses that he has "no idea" concerning its meaning. Yet it surely must have a lurking, subconscious import for him because it emerges time and again in his work.

Casselli believes that it is useless to assign a narrative to his paintings; that "each viewer sees, feels and interprets anew."